What Is Little Orphan Annie Hand Drawn Strip Art Worth

| Little Orphan Annie | |

|---|---|

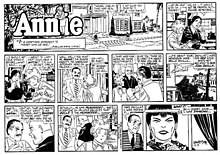

Cupples & Leon collection (1933) | |

| Author(south) | Harold Grey |

| Electric current status/schedule | Ended |

| Launch appointment | August 5, 1924 |

| Stop date | June thirteen, 2010 |

| Syndicate(southward) | Tribune Media Services |

| Genre(south) | Humor, Activeness, Run a risk |

Little Orphan Annie is a daily American comic strip created by Harold Grey and syndicated by the Tribune Media Services. The strip took its name from the 1885 poem "Little Orphant Annie" by James Whitcomb Riley, and it made its debut on Baronial 5, 1924, in the New York Daily News.

The plot follows the wide-ranging adventures of Annie, her dog Sandy and her benefactor Oliver "Daddy" Warbucks. Secondary characters include Punjab, the Asp and Mr. Am. The strip attracted adult readers with political commentary that targeted (amidst other things) organized labor, the New Deal and communism.

Following Gray's death in 1968, several artists drew the strip and, for a time, "classic" strips were reruns. Fiddling Orphan Annie inspired a radio show in 1930, film adaptations by RKO in 1932 and Paramount in 1938 and a Broadway musical Annie in 1977 (which was adapted on screen four times, one in 1982, one on Boob tube in 1999, one in 2014 and some other a live Telly production in 2021). The strip's popularity declined over the years; it was running in just 20 newspapers when it was cancelled on June thirteen, 2010. The characters now announced occasionally as supporting cast in Dick Tracy.

Story [edit]

Little Orphan Annie displays literary kinship with the picaresque novel in its seemingly countless string of episodic and unrelated adventures in the life of a character who wanders similar an innocent vagabond through a decadent world. In Annie's starting time year, the picaresque pattern that characterizes her story is gear up, with the major players – Annie, Sandy and "Daddy" Warbucks – introduced within the strip'south first several weeks.

The story opens in a dreary and Dickensian orphanage where Annie is routinely abused by the cold and sarcastic matron Miss Asthma, who eventually is replaced by the equally hateful Miss Treat (whose name is a play on the discussion "mistreat").

One 24-hour interval, the wealthy but hateful-spirited Mrs. Warbucks takes Annie into her home "on trial". She makes it clear that she does not like Annie and tries to send her back to "the Home", but one of her society friends catches her in the act, and immediately, to her disgust, she changes her listen.

Her husband Oliver, who returned from a concern trip, instantly develops a paternal affection for Annie and instructs her to address him as "Daddy". Originally, the Warbucks had a domestic dog named Ane-Lung, who liked Annie. Their household staff also takes to Annie and they like her.

Nevertheless, the staff despises Mrs. Warbucks, the girl of a nouveau riche plumber's assistant. Common cold-hearted Mrs. Warbucks sends Annie back to "the Habitation" numerous times, and the staff hates her for that. "Daddy" (Oliver) keeps thinking of her as his daughter. Mrs. Warbucks often argues with Oliver over how much he "mortifies her when company comes" and his affection for Annie. A very status-witting woman, she feels that Oliver and Annie are ruining her socially. However, Oliver usually is able to put her in her place, peculiarly when she criticizes Annie.

Story formulas [edit]

The strip adult a series of formulas that ran over its course to facilitate a broad range of stories. The earlier strips relied on a formula by which Daddy Warbucks is called away on business organization and through a variety of contrivances, Annie is cast out of the Warbucks mansion, usually by her enemy, the nasty Mrs. Warbucks. Annie so wanders the countryside and has adventures meeting and helping new people in their daily struggles. Early stories dealt with political abuse, criminal gangs and corrupt institutions, which Annie would confront. Annie ultimately would encounter troubles with the villain, who would be vanquished by the returning Daddy Warbucks. Annie and Daddy would then be reunited, at which point, subsequently several weeks, the formula would play out again. In the series, each strip represented a single mean solar day in the life of the characters. This device was dropped by the cease of the '20s.

By the 1930s, during the Great Depression, the formula was tweaked: Daddy Warbucks lost his fortune due to a corrupt rival and briefly died from despair at the 1944 re-election of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Annie remained an orphan, and for several years had adventures that involved more than internationally based enemies. The contemporary events taking place in Europe were reflected in the strips during the 1940s and World State of war 2. Daddy Warbucks was reunited with Annie, as his death was retconned to coma, from which he woke in 1945, congruent with Roosevelt'south existent-world death.

Past this fourth dimension, the serial enlarged its world with the addition of characters such as Asp and Punjab, bodyguards and servants to Annie and Daddy Warbucks. They traveled the world, with Annie having adventures on her ain or with her adopted family unit.

Characters [edit]

Annie is a ten-year-old orphan. Her distinguishing physical characteristics are auburn curly locks, a red dress and vacant circles for eyes. Her catchphrases are "Gee whiskers" and "Leapin' lizards!" Annie attributes her lasting youthfulness to her altogether being on October fifteen. Annie is a plucky, generous, compassionate, and optimistic youngster who can concur her ain against bullies, and has a strong and intuitive sense of correct and wrong.

Sandy enters the story in a January 1925 strip as a puppy of no particular brood which Annie rescues from a gang of abusive boys. The girl is working as a drudge in Mrs. Bottle's grocery store at the time and manages to keep the puppy briefly curtained. She finally gives him to Paddy Lynch, a gentle man who owns a "steak joint" and tin give Sandy a good home. Sandy is a mature dog when he suddenly reappears in a May 1925 strip to rescue Annie from gypsy kidnappers. Annie and Sandy remain together thereafter.

Oliver "Daddy" Warbucks first appears in a September 1924 strip and reveals a calendar month later on he was formerly a small-scale machine shop owner who acquired his enormous wealth producing munitions during Globe War I. He is a large, powerfully-built bald man, the arcadian capitalist, who typically wears a tuxedo and diamond stickpin in his shirtfront. He likes Annie at one time, instructing her to call him "Daddy", but his wife (the girl of a plumber's assistant) is a snobbish, gossiping nouveau riche who derides her husband's affection for Annie. When Warbucks is all of a sudden called to Siberia on business, his wife spitefully sends Annie back to the orphanage.

Other major characters include Warbucks' correct-mitt men: Punjab, an eight-foot native of India, introduced in 1935, and the Asp, an inscrutably generalized East Asian, who outset appeared in 1937. Also introduced in 1937 was the mysterious Mr. Am, a disguised sage millions-of-years sometime, whose supernatural powers include bringing the dead back to life.

Publication history [edit]

The outset strip of Annie'south test run, published on August v, 1924.

Afterward World State of war I, cartoonist Harold Grayness joined the Chicago Tribune which, at that time, was existence reworked by owner Joseph Medill Patterson into an important national journal. Equally function of his plan, Patterson wanted to publish comic strips that would lend themselves to nationwide syndication and to movie and radio adaptations. Grayness's strips were consistently rejected by Patterson, but Little Orphan Annie was finally accepted and debuted in a test run on August 5, 1924, in the New York Daily News, a Tribune-endemic tabloid. Reader response was positive, and Annie began appearing as a Sunday strip in the Tribune on November ii and as a daily strip on November 10. It was soon offered for syndication and picked up by the Toronto Star and The Atlanta Constitution.[1]

Gray reported in 1952 that Annie's origin lay in a chance meeting he had with a ragamuffin while wandering the streets of Chicago looking for cartooning ideas. "I talked to this petty child and liked her right away", Grayness said. "She had common sense, knew how to take care of herself. She had to. Her name was Annie. At the time some 40 strips were using boys every bit the main characters; only three were using girls. I chose Annie for mine, and made her an orphan, so she'd have no family, no tangling alliances, but freedom to go where she pleased."[1] By changing the gender of his pb graphic symbol, Gray differentiated himself in the field of comics (and probable increased his readership by appealing to female readers).[2] In designing the strip, Gray was influenced by his midwestern subcontract boyhood, Victorian poetry and novels such as Charles Dickens'due south Great Expectations, Sidney Smith'due south wildly popular comic strip The Gumps, and the histrionics of the silent films and melodramas of the menstruation. Initially, there was no continuity between the dailies and the Sun strips, simply by the early 1930s the two had go one.[1] The strip (whose title was borrowed from James Whitcomb Riley'southward 1885 poem "Picayune Orphant Annie") was "conservative and topical", according to the editors of The Great Depression in America: A Cultural Encyclopedia, and "represents the personal vision" of Gray and Riley's "homespun philosophy of hard piece of work, respect for elders, and a cheerful outlook on life". A Fortune popularity poll in 1937 indicated Piffling Orphan Annie ranked number i and alee of Popeye, Dick Tracy, Bringing Upward Father, The Gumps, Blondie, Moon Mullins, Joe Palooka, Li'50 Abner and Tillie the Toiler.[iii]

1929 to World War II [edit]

Gray was little afflicted by the stock market crash of 1929. The strip was more pop than ever and brought him a good income, which was just enhanced when the strip became the basis for a radio program in 1930 and two films in 1932 and 1938. Predictably, Gray was reviled by some for preaching in the strip to the poor about difficult work, initiative, and motivation while living well on his income.

Starting January 4, 1931, Greyness added a topper strip to the Lilliputian Orphan Annie Sunday page called Private Life Of... The strip chose a mutual object each week like potatoes, hats and baseballs, and told their "stories". That thought ran for two years, ending on Christmas Mean solar day, 1932. A new three-panel gag strip nearly an elderly lady, Maw Green, began on January 1, 1933, and ran along the bottom of the Sun folio until 1973.[4]

In 1935 Punjab, a gigantic, sword-wielding, beturbaned Indian, was introduced to the strip and became one of its iconic characters. Whereas Annie's adventures up to the point of Punjab'south appearance were realistic and believable, her adventures following his introduction touched upon the supernatural, the cosmic, and the fantastic.[five]

In November 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected president and proposed his New Bargain. Many, including Greyness, saw this and other programs as government interference in private enterprise. Gray railed confronting Roosevelt and his programs. (Gray even seemingly killed Daddy Warbucks off in 1945, suggesting that Warbucks could not coexist in the earth with FDR. Only following FDR's death, Grayness brought back Warbucks, who said to Annie, "Somehow I feel that the climate hither has changed since I went abroad."[6]) Annie's life was complicated non just past thugs and gangsters simply likewise by New Bargain exercise-gooders and bureaucrats. Organized labor was feared by businessmen and Grayness took their side. Some writers and editors took issue with this strip's criticisms of FDR's New Deal and 1930s labor unionism. The New Republic described Annie as "Hooverism in the Funnies", arguing that Gray'southward strip was defending utility company bosses and so existence investigated by the government.[7] The Herald Dispatch of Huntington, West Virginia stopped running Little Orphan Annie, press a front-page editorial rebuking Grey's politics.[8] A subsequent New Republic editorial praised the paper'due south motion,[9] and The Nation likewise voiced its back up.[x]

Showtime Little Orphan Annie Sunday folio (November 2, 1924)

In the belatedly 1920s, the strip had taken on a more adult and adventurous feel with Annie encountering killers, gangsters, spies, and saboteurs. It was about this fourth dimension that Gray, whose politics seem to have been broadly conservative and libertarian with a decided populist streak, introduced some of his more than controversial storylines. He would look into the darker aspects of human nature, such as greed and treachery. The gap between rich and poor was an of import theme. His hostility toward labor unions was dramatized in the 1935 story "Eonite". Other targets were the New Bargain, communism, and decadent businessmen.[eleven]

Greyness was especially critical of the justice system, which he saw as not doing plenty to deal with criminals. Thus, some of his storylines featured people taking the police into their own hands. This happened as early as 1927 in an adventure named "The Haunted House". Annie is kidnapped by a gangster called Mister Mack. Warbucks rescues her and takes Mack and his gang into custody. He then contacts a local Senator who owes him a favor. Warbucks persuades the politico to use his influence with the judge and brand certain that the trial goes their way and that Mack and his men become their just desserts. Annie questions the apply of such methods but concludes, "With all th' crooks usin' pull an' money to get off, I guess 'bout th' only way to become 'em punished is for honest constabulary similar Daddy to utilize pull an' money an' gun-men, too, an' beat them at their own game."

Warbucks became much more ruthless in subsequently years. After communicable yet another gang of Annie kidnappers he announced that he "wouldn't recollect of troubling the police with you boys", implying that while he and Annie celebrated their reunion, the Asp and his men took the kidnappers abroad to be lynched. In another Lord's day strip, published during Earth War Ii, a war-profiteer expresses the hope that the disharmonize would last some other 20 years. An outraged member of the public physically assaults the man for his opinion, claiming revenge for his two sons who have already been killed in the fighting. When a passing policeman is about to intervene, Annie talks him out of it, suggesting, "Information technology's meliorate some times to let folks settle some questions by what you might call democratic processes."

Globe War II and Annie's Junior Commandos [edit]

As war clouds gathered, both the Chicago Tribune and the New York Daily News advocated neutrality; "Daddy" Warbucks, notwithstanding, was gleefully manufacturing tanks, planes, and munitions. Announcer James Edward Vlamos deplored the loss of fantasy, innocence, and humor in the "funnies", and took to task one of Grayness'south sequences about espionage, noting that the "fate of the nation" rested on "Annie's frail shoulders". Vlamos advised readers to "Stick to the saner world of war and horror on the front pages."[12]

When the Usa entered World War Two, Annie non only played her part by bravado up a German submarine merely organized and led groups of children called the Junior Commandos in the collection of newspapers, fleck metallic, and other recyclable materials for the state of war try. Annie herself wore an armband emblazoned with "JC" and chosen herself "Colonel Annie". In real life, the idea caught on, and schools and parents were encouraged to organize similar groups. Twenty 1000 Junior Commandos were reportedly registered in Boston.[12]

Greyness was praised far and broad for his state of war effort abstraction. Editor & Publisher wrote,

Harold Grayness, Piddling Orphan Annie creator, has done one of the biggest jobs to appointment for the scrap drive. His 'Junior Commando' project, which he inaugurated some months ago, has caught on all around the country, and tons of scrap have been collected and contributed to the campaign. The kids sell the scrap, and the proceeds are turned into stamps and bonds.[13]

Not all was rosy for Gray, however. He applied for actress gas coupons, reasoning that he would demand them to drive nigh the countryside collecting plot cloth for the strip. Only an Office of Price Administration clerk named Flack refused to give Grayness the coupons, explaining that cartoons were not vital to the war effort. Grey requested a hearing and the original decision was upheld. Gray was furious and vented in the strip, with especial venom directed at Flack (thinly disguised equally a graphic symbol named "Fred Flask"), regime price controls, and other concerns. Grayness had his supporters, but Flack'south neighbors dedicated him in the local newspaper and tongue-lashed Gray. Flack threatened to sue for libel, and some papers cancelled the strip. Grayness showed no remorse, but did discontinue the sequence.[12]

Grayness was criticized by a Southern paper for including a black youngster among the white children in the Junior Commandos. Grayness made it clear he was not a reformer, did not believe in breaking down the colour line, and was no relation to Eleanor Roosevelt, an ardent supporter of civil rights. He pointed out that Annie was a friend to all, and that most cities in the North had "large dark towns". The inclusion of a black character in the Junior Commandos, he explained, was "merely a coincidental gesture toward a very large cake of readers." African American readers wrote letters to Grayness thanking him for the incorporation of a black child in the strip.[12]

In the summertime of 1944 Franklin Delano Roosevelt was nominated for a fourth term as President of the United States, and Gray (who had little honey for Roosevelt) killed off Warbucks in a month-long sequence of sentimental pathos. Readers were more often than not unhappy with Gray's decision, but some liberals advocated the same fate for Annie and her "stale philosophy". Past the following November withal, Annie was working as a maid in a Mrs. Bleating-Hart's habitation and suffering all sorts of torments from her mistress. The public begged Gray to have mercy on Annie, and he had her framed for her mistress's murder. She was exonerated. Post-obit Roosevelt's expiry in April 1945, Gray resurrected Warbucks (who was only playing expressionless to thwart his enemies) and once more the billionaire began expounding the joys of capitalism.[12]

Post-war years [edit]

In the post-state of war years, Annie took on The Bomb, communism, teenage rebellion and a host of other social and political concerns, often provoking the enmity of clergymen, union leaders and others. For example, Grayness believed children should be allowed to work. "A little work never hurt any kid," Gray affirmed, "Ane of the reasons we take and then much juvenile delinquency is that kids are forced by law to loaf around on street corners and go into trouble." His conventionalities brought upon him the wrath of the labor movement, which staunchly supported the child labor laws.[12]

A London newspaper columnist thought some of Gray'south sequences a threat to earth peace, but a Detroit newspaper supported Gray on his "shoot first, ask questions later" foreign policy. Grey was criticized for the gruesome violence in the strips, particularly a sequence in which Annie and Sandy were run over by a car. Gray responded to the criticism by giving Annie a year-long bout with amnesia that allowed her to trip through several adventures without Daddy. In 1956, a sequence well-nigh juvenile delinquency, drug addiction, switchblades, prostitutes, crooked cops, and the ties between teens and adult gangsters unleashed a firestorm of criticism from unions, the clergy and intellectuals with 30 newspapers cancelling the strip. The syndicate ordered Grayness to drib the sequence and develop another risk.[12]

Grayness'southward death [edit]

Gray died in May 1968 of cancer, and the strip was connected under other cartoonists. Gray'south cousin and assistant Robert Leffingwell was the showtime on the job but proved inadequate and the strip was handed over to Tribune staff creative person Henry Arnold and general director Henry Raduta as the search connected for a permanent replacement. Tex Blaisdell, an experienced comics artist, got the job with Elliot Caplin as writer. Caplin avoided political themes and full-bodied instead on character stories. The two worked together 6 years on the strip, merely subscriptions savage off and both left at the stop of 1973. The strip was passed to others and during this time complaints were registered regarding Annie'southward appearance, her bourgeois politics, and her lack of spunk. Early in 1974, David Lettick took the strip, but his Annie was drawn in an entirely different and more "cartoonish" manner, leading to reader complaints, and he left after only three months. In April 1974, the decision was made to reprint Gray'south classic strips, beginning in 1936. Subscriptions increased.[12] The reprints ran from April 22, 1974, to Dec viii, 1979.[14]

Following the success of the Broadway musical Annie, the strip was resurrected on December 9, 1979, as Annie, written and drawn by Leonard Starr.[xiv] Starr, the creator of Mary Perkins, On Phase, was the only one besides Gray to accomplish notable success with the strip.

Starr's last strip ran on February xx, 2000, and the strip went into reprints again for several months.[fourteen] Starr was succeeded by Daily News writer Jay Maeder and artist Andrew Pepoy, showtime Monday, June v, 2000. Pepoy was eventually succeeded past Alan Kupperberg (Apr 1, 2001 – July xi, 2004) and Ted Slampyak (July 5, 2004 – June xiii, 2010).[fourteen] The new creators updated the strip's settings and characters for a mod audience, giving Annie a new hairdo and jeans rather than her trademark dress. However, Maeder'due south new stories never managed to live up to the desolation and emotional engagement of the stories by Gray and Starr. Annie herself was often reduced to a supporting role, and she was a far less complex character than the girl readers had known for 7 decades. Maeder'due south writing style also tended to make the stories feel like tongue-in-cheek adventures compared to the serious, heartfelt tales Gray and Starr favored. Annie gradually lost subscribers during the 2000s, and, past 2010, information technology was running in fewer than 20 U.S. newspapers.

Cancellation [edit]

On May thirteen, 2010, Tribune Media Services appear that the strip's final installment would announced on Lord's day, June 13, 2010, ending after 86 years.[15] At the fourth dimension of the cancellation announcement, it was running in fewer than 20 newspapers, some of which, such as the New York Daily News, had carried the strip for its entire life. The final cartoonist, Ted Slampyak, said, "It'due south kind of painful. It's almost like mourning the loss of a friend."[xvi]

The final strip was the culmination of a story arc where Annie was kidnapped from her hotel by a wanted state of war criminal from eastern Europe who checked in under a phony proper noun with a imitation passport. Although Warbucks enlists the help of the FBI and Interpol to observe her, by the cease of the final strip he has begun to resign himself to the very strong possibility that Annie most likely will non be constitute alive. Unfortunately, Warbucks is unaware that Annie is yet alive and has made her mode to Guatemala with her captor, known simply as the "Butcher of the Balkans". Although Annie wants to be let get, the Butcher tells her that he neither will let her go nor impale her—for fear of existence captured and because he will not impale a child despite his many political killings—and adds that she has a new life now with him. The concluding panel of the strip reads "And this is where we leave our Annie. For At present—".

Since the cancellation, rerun strips have been running on the GoComics site.

Final resolution: Warbucks calls on Dick Tracy [edit]

In 2013, the squad behind Dick Tracy began a story line that would permanently resolve the fate of Annie. The week of June 10, 2013, featured several Annie characters in extended cameos complete with dialogue, including Warbucks, the Asp and Punjab. On June 16, Warbucks implies that Annie is still missing and that he might even enlist Tracy's help in finding her.[17] Asp and Punjab appeared over again on March 26, 2014. The caption says that these events will soon impact on the detective.[eighteen]

The storyline resumed on June 8, 2014, with Warbucks asking for Tracy's help in finding Annie.[xix] In the grade of the story, Tracy receives a letter from Annie and determines her location. Meanwhile, the name of the kidnapper is revealed equally Henrik Wilemse, and he has been tracked to the city where he is found and made to disappear. Tracy and Warbucks rescued Annie, and the storyline wrapped upward on October 12.[20]

Annie again visited Dick Tracy, visiting his granddaughter Honeymoon Tracy, starting June 6, 2015.[21] This arc concluded Sept. 26 2015 with Dick Tracy sending the girls habitation from a law-breaking scene to go on them out of the news.

A third appearance of Annie and her supporting cast in Dick Tracy's strip began on May 16, 2019, and involves both B-B Eyes' murder and doubts about the fate of Trixie.[22] The arc also establishes that Warbucks has formally adopted Annie, every bit opposed to beingness just his ward.[23]

Adaptations [edit]

Radio [edit]

Footling Orphan Annie was adjusted to a 15-infinitesimal radio show that debuted on WGN Chicago in 1930 and went national on NBC's Blue Network start April 6, 1931.[24] [25] The show was one of the beginning comic strips adjusted to radio, attracted about 6 million fans, and left the air in 1942.[24] [25] Radio historian Jim Harmon attributes the show'due south popularity in The Groovy Radio Heroes to the fact that it was the only radio show to deal with and appeal to young children.[24]

1930s films based on the comic strip [edit]

Two film adaptations were released at the height of Annie's popularity in the 1930s. Little Orphan Annie, the first adaptation, was produced past David O. Selznick for RKO in 1932 and starred Mitzi Green as Annie. The plot was elementary: Warbucks leaves on concern and Annie finds herself in the orphanage again. She pals effectually with a little boy named Mickey, and when he is adopted by a wealthy adult female, she visits him in his new home. Warbucks returns and holds a Christmas political party for all. The film opened on Christmas Eve 1932. Multifariousness panned it, and the New York Daily News was "slightly disappointed" with the film, thinking Dark-green too "big and buxom" for the role.[12] Paramount brought Ann Gillis to the function of Annie in their 1938 film accommodation, merely this version was panned as well. One reviewer idea it "stupid and thoroughly boresome" and was uncomfortable with the "sugar-coated Pollyanna characterization" given Annie.[12]

Three years afterwards the RKO release, Gray wrote a sequence for the strip that sent Annie to Hollywood. She is hired at depression wages to play the stand-in and stunt double for the bratty child star Tootsie McSnoots. Young starlet Janey Spangles tips off Annie to the corrupt practices in Hollywood. Annie handles the information with maturity and has a proficient time with Janey while doing her job on the gear up. Annie doesn't go a star. Every bit Bruce Smith remarks in The History of Little Orphan Annie, "Gray was smart enough never to let [Annie] go besides successful."[12]

Broadway [edit]

In 1977, Little Orphan Annie was adapted to the Broadway phase as Annie. With music by Charles Strouse, lyrics by Martin Charnin and book by Thomas Meehan, the original production ran from Apr 21, 1977, to January 2, 1983. The piece of work has been staged internationally. The musical took considerable liberties with the original comic strip plot.

The Broadway Annies were Andrea McArdle, Shelly Bruce, Sarah Jessica Parker, Allison Smith and Alyson Kirk. Actresses who portrayed Miss Hannigan are Dorothy Loudon, Alice Ghostley, Betty Hutton, Ruth Kobart, Marcia Lewis, June Havoc, Nell Carter and Sally Struthers. Songs from the musical include "Tomorrow" and "It's the Hard Knock Life". There is also a children'southward version of Annie chosen Annie Junior. Two sequels to the musical, Annie 2: Miss Hannigan's Revenge (1989) and Annie Warbucks (1992-93), were written by the aforementioned artistic team; neither show opened on Broadway. At that place were likewise many "bus & truck" tours of Little Orphan Annie throughout the Us during the success of the Broadway Shows.

Film adaptations of the Broadway musical [edit]

In addition to the ii Annie films of the 1930s, there have been three picture show adaptations of the Broadway play. All take the aforementioned title. They are Annie (1982), Annie (1999, a made-for-tv set adaptation) and Annie (2014).

The 1982 version was directed past John Huston and starred Aileen Quinn every bit Annie, Albert Finney equally Warbucks, Ann Reinking as his secretary Grace Farrell, and Carol Burnett as Miss Hannigan. The film departed from the Broadway product in several respects, most notably changing the climax of the story from Christmas to the Fourth of July. It as well featured five new songs, "Dumb Dog", "Sandy", "Permit's Go to the Movies", "Sign", and "We Got Annie", while cutting "We'd similar to Thanks, Herbert Hoover", "N.Y.C", "Y'all Won't Be an Orphan for Long", "Something Was Missing", "Annie", and "New Deal for Christmas". Information technology received mixed critical reviews and, while becoming the 10th highest-grossing film of 1982, barely recouped its $fifty one thousand thousand budget.

A straight-to-video film, Annie: A Royal Adventure! was released in 1996 as a sequel to the 1982 film. It features Ashley Johnson as Annie and focuses on the adventures of Annie and her friends Hannah and Molly. Information technology is set in England in 1943, about 10 years after the showtime film, when Annie and her friends Hannah and Molly canvas to England afterwards Daddy Warbucks is invited to receive a knighthood. None of the original 1982 cast appear and the film features no musical numbers apart from a reprise of "Tomorrow".

The animated Little Orphan Annie's A Very Animated Christmas was produced as a straight-to-video picture show in 1995.[26]

The 1999 television film was produced for The Wonderful World of Disney. Information technology starred Victor Garber, Alan Cumming, Audra McDonald and Kristin Chenoweth, with Oscar winner Kathy Bates every bit Miss Hannigan and newcomer Alicia Morton equally Annie. While its plot stuck closer to the original Broadway production, it likewise omitted "Nosotros'd Like to Thank You, Herbert Hoover", "Annie", "New Deal for Christmas", and a reprise of "Tomorrow." Generally favorably received, the product earned two Emmy Awards and George Foster Peabody Award.

The 2014 motion picture Annie was produced by Jay-Z and Will Smith. It starred Quvenzhané Wallis in the championship role and Jamie Foxx in the part of Will Stacks (a role similar to Warbucks). The movie follows the basic plot of the musical but is set in the present day and features new songs along re-mixed versions of older ones. Information technology was released on December 19, 2014.

Parodies, imitations and cultural citations [edit]

- The name Little Orphan Annie lends itself easily to parody. Many comics, cartoons, Boob tube shows and other media take played off information technology. Some examples include Walt Kelly in Pogo (as "Little Arf 'northward Nonnie" and later "Lulu Arfin' Nanny"); past Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood in Mad #ix as "Little Orphan Melvin", while Kurtzman later on produced a long-running erotic comic for Playboy chosen Little Annie Fanny; in The Fabled Furry Freak Brothers, Gilbert Shelton satirized the strip as "Niggling Orphan Amphetamine"; the terminate-movement goggle box serial Robot Chicken in which Little Orphan Annie fails to grasp the true meaning of a hard knock life; 1980s children'south program You Can't Exercise That on Television in its later banned "Adoption" episode, parodied the graphic symbol as "Little Orphan Andrea"; the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comics past Mirage Studios characteristic a fictional toy line named "Little Orphan Aliens"[27]

- Between 1936 and October 17, 1959, the comic strip Belinda Blue-Optics (later shortened to Belinda) ran in the Great britain in the Daily Mirror. Writers Pecker Connor and Don Freeman and artists Stephen Dowling and Tony Royle all worked on the strip over the years. In The Penguin Book of Comics Belinda is described every bit "a perpetual waif, a British counterpart to the transatlantic Petty Orphan Annie."[28] [29]

- The strip also influenced Piffling Annie Rooney (January. 10, 1927–1966) and Frankie Putter (1934-1938).

- In 1995, Lilliputian Orphan Annie was one of 20 American comic strips included in the Comic Strip Classics series of commemorative U.S. postage stamps.

- Children's television host Chuck McCann became well known in the New York/New Jersey market for his imitations of newspaper comic characters; McCann put blank white circles over his eyes during his impression of Annie.

- In the 1983 motion picture A Christmas Story, the main character Ralph is a fan of the Little Orphan Annie radio drama, listening to the show religiously while waiting for his Ovaltine decoder pivot.

- Rapper Jay-Z has referenced Little Orphan Annie in at least two of his songs,[30] [31] as well as sampling "Information technology's the Difficult Knock Life" for "Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Canticle)".

- On the album encompass of punk stone cover band Me First and the Gimme Gimmes' 1999 anthology Are a Drag, rhythm guitarist and Lagwagon vocalist Joey Cape is dressed as Annie, equally she was depicted in the 1982 film.

- In the movie Bad Teacher, Elizabeth (Cameron Diaz) wears a "Little Orphan Annie's wig" when she tries to seduce a human being.

- Starting in 2014, gingerlock comedian Michelle Wolf appeared on numerous segments on Late Night as her fictional persona, "Grown-Up Annie", an adult version of Petty Orphan Annie.[32] [33]

In medicine, "Orphan Annie eye" (empty or "ground drinking glass") nuclei are a feature histological finding in papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland.

Archives [edit]

Harold Grayness's piece of work is in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Enquiry Center at Boston Academy. The Gray drove includes artwork, printed material, correspondence, manuscripts and photographs. Grey's original pen and ink drawings for Little Orphan Annie daily strips appointment from 1924 to 1968. The Sunday strips engagement from 1924 to 1964. Printed material in the collection includes numerous proofs of Little Orphan Annie daily and Sunday strips (1925–68). Virtually of these are in bound volumes. There are proofsheets of Little Orphan Annie daily strips from the Chicago Tribune-New York Times Syndicate, Inc. for the dates 1943, 1959–61 and 1965–68, every bit well as originals and photocopies of the printed versions of Little Orphan Annie, both daily and Sunday strips.[34]

Episode guide [edit]

- 1924: From Rags to Riches (and Back Once again); Just a Couple of Hurried Bites

- 1925: The Silos; Count De Tour

- 1926: Schoolhouse of Hard Knocks; Under the Large Peak; Will Tomorrow Never Come?

- 1927: The Blue Bell of Happiness; Haunted House; Other People's Troubles

- 1928: Sherlock, Jr.; Mush and Milk; Simply Before the Dawn

- 1929: Farm Relief; Daughter Next Door; One Blunder Later on Some other

- 1930: 7 Year Itch; The Frame, the Farm & the Flood; Shipwrecked

- 1931: Busted!; Good Neighbor Policy; Down, But Not Out; And a Blind Man Shall Lead Them; Distant Relations; A Hundred to One

- 1932: Don't Mess with Cupid; They Call Her Large Mama; A House Divided; Cosmic City

- 1933: Pinching Pennies; Retribution; Who'd Chizzle a Blind Human?

- 1934: Bleek House; Phil O. Blustered; The One-Way Road to Justice; Dust Yourself Off

- 1935: Punjab the Wizard; Beware the Hate Mongers; Annie in Hollywood

- 1936: Inkey; On the Lam; The Sole of the Matter; The Gila Story; Those Who are About to Dice

- 1937: The Million-Dollar Vocalism; The Almighty Mr. Am; Into the Fourth dimension; Easy Money

- 1938: A Rose, per Take chances; The Last Port of Call; Men in Black

- 1939: At Home on the Range; Assault on the Hacienda; Three Face E; Justice at Play

- 1940: In the Nick of Time; Billy the Child; Peg O' their Hearts

- 1941: The Happy Warrior; Saints and Cynics; Never Trouble Problem; On Needles and Pins

- 1942: The Junior Commandos; Out on a Limb

- 1943: The Rat Trap, Adjacent Stop—Gooneyville

- 1944: In a Den of Thieves, Death exist Thy Name, Mrs. Bleating-Heart

- 1950: Ivan the Terrible, The Town Called Fiasco, Circumstantial Prove

- 1951: Open Season for Trouble, Something to Call back

- 1952: Here Today, Gone Tomorrow, Dead Men'southward Point, When You Do That Hoodoo, A Town Called Futility

Reprints [edit]

- Between 1926 and 1934, Cupples & Leon published nine collections of Annie strips:

- Little Orphan Annie (1925 strips, reprinted by Dover and Pacific Comics Guild)

- In the Circus (1926 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Club)

- Haunted Firm (1927 strips, reprinted past Pacific Comics Club)

- Bucking the World (1928 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Social club and in Nemo # 8)

- Never Say Die (1929 strips, reprinted past Pacific Comics Lodge)

- Shipwrecked (1930 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Lodge)

- A Willing Helper (1931 strips, reprinted by Pacific Comics Gild)

- In Cosmic City (1932 strips, reprinted by Dover)

- Uncle Dan (1933 strips, reprinted past Pacific Comics Club)

- Arf: The Life and Hard Times of Little Orphan Annie (1970): reprints approximately half the daily strips from 1935 to 1945. However, many of the storylines are edited and shortened, with gaps of several months between some strips.

- Dover Publications reprinted ii of the Cupples & Leon books and an original collection Trivial Orphan Annie in the Great Depression which contains all the daily strips from January to September, 1931.

- Pacific Comics Guild has reprinted eight of the Cupples & Leon books. They have also published a new series of reprints, with complete runs of daily strip, in the same format at the C&L books, roofing some of the daily strips from 1925 to 29:

- The Judgement, 1925 strips

- The Dreamer, strips from Jan 22, 1926, to April thirty, 1926

- Daddy, strips from September 6, 1926, to Dec iv, 1926.

- The Hobo, strips from December six, 1926, to March 5, 1927.

- Rich Man, Poor Man, strips from March seven, 1927, to May 7, 1927.

- The Little Worker, strips from October eight, 1927, to December 21, 1927.

- The Business of Giving, strips from November 23, 1928, to March two, 1929.

- This Surprising World, strips from March four, 1929, to June 11, 1929.

- The Pro and the Con, strips from June 12, 1929, to September nineteen, 1929.

- The Homo of Mystery, strips from September 20, 1929, to December 31, 1929.

Because both Cupples & Leon and Pacific Comics Lodge, the biggest gap is in 1928.

- All of the daily and Sun strips from 1931 to 1935 were reprinted by Fantagraphics in the 1990s, in five volumes, each covering a year, from 1931 to 1935.

- Picking up where Fantagraphics left off, Comics Revue magazine reprinted both daily and Sunday strips from 1936 to 1941, starting in Comics Revue #167 and ending in #288.

- Pacific Comics Society reprinted approximately the first 6 months of the strips from Comics Revue, under the title Home at Concluding, December 29, 1935 to April 5, 1936.

- Dragon Lady Press reprinted daily and Sunday strips from September 3, 1945, to February 9, 1946.

In 2008, IDW Publishing started a reprint series, The Complete Petty Orphan Annie, under its The Library of American Comics imprint.[35]

Run across as well [edit]

- Punky Brewster, a boob tube series, about an abased girl with her foster dad, and the friends she meets. Also had a spin-off cartoon series.

References [edit]

- ^ a b c Gray Harold (2008). The Complete Little Orphan Annie Volume Ane: Will Tomorrow Ever Come? Daily Comics 1924–1927. IDW Publishing. pp. 23–7. ISBN978-1-60010-140-3.

- ^ Maurer, Elizabeth (2017), Little Orphan Annie to the Rescue: Depression-era Heroine Defied Gender Stereotypes https://www.womenshistory.org/articles/petty-orphan-annie-rescue

- ^ Young, William H. & Nancy K. (2007). The Great Low in America: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Greenwood. pp. 107, 297–8.

- ^ Holtz, Allan (2012). American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. pp. 256 & 321. ISBN9780472117567.

- ^ Gray, Harold; Heer, Jeet (2010). Punjab and Politics. The complete Little Orphan Annie Book Six: Punjab the Sorcerer Daily and Dominicus Comics 1935–1936. IDW Publishing. pp. five–xiii. ISBN978-1-60010-792-4.

- ^ ""Big Deals: Comics' Highest-Contour Moments," Hogan's Aisle #vii, 1999". Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- ^ Neuberger, Richard L. (July xi, 1934). "Hooverism in the Funnies". The New Republic. p. 23.

- ^ Clendenin, James. Herald Dispatch: one.

- ^ "Fascism in the Funnies". The New Republic. September 18, 1935. p. 147.

- ^ "Little Orphan Annie". The Nation. October 23, 1935.

- ^ Cagle, Daryl. "The New Bargain Kills Daddy Warbucks".

- ^ a b c d e f one thousand h i j k Smith, Bruce (1982). The History of Piddling Orphan Annie. Ballantine Books. pp. 43–63. ISBN0-345-30546-9.

- ^ Monchak, S. J. (September 19, 1942). "State of war Work of the Cartoonists: Cartoonists Important Cistron In Keeping Nation's Morale". Editor & Publisher.

- ^ a b c d Holtz, Allan (2012). American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The Academy of Michigan Printing. p. 241. ISBN9780472117567.

- ^ Rosenthal, Phil (May xiii, 2010). "Annie left a homeless orphan in newspaper world". Chicago Tribune . Retrieved Feb 9, 2011.

- ^ McShane, Larry (May 13, 2010). "'Piddling Orphan Annie' comic canceled past Tribune Media Services". Daily News . Retrieved Feb 9, 2011.

- ^ "Dick Tracy past Joe Staton and Mike Curtis for Jun xvi, 2013 - GoComics.com". June xvi, 2013.

- ^ "Dick Tracy by Joe Staton and Mike Curtis for Mar 26, 2014 - GoComics.com". March 26, 2014.

- ^ "Dick Tracy by Joe Staton and Mike Curtis for Jun 8, 2014 - GoComics.com". June 8, 2014.

- ^ "Dick Tracy by Joe Staton and Mike Curtis for Oct 12, 2014 - GoComics.com". October 12, 2014.

- ^ "Dick Tracy by Joe Staton and Mike Curtis for Jun half dozen, 2015 - GoComics.com". June 6, 2015.

- ^ "Dick Tracy past Joe Staton and Mike Curtis for May sixteen, 2019 - GoComics.com". May sixteen, 2019.

- ^ Curtis, Joe Staton and Mike (July nine, 2019). "Dick Tracy by Joe Staton and Mike Curtis for July 09, 2019 | GoComics.com". GoComics . Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ a b c Harmon, Jim (2001). The Great Radio Heroes. McFarland. pp. 82–5. ISBN978-0-7864-0850-4.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Claudia A., and Jacqueline Reid-Walsh (Eds.) (2007). Girl Civilisation: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood. p. 402.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crump, William D. (2019). Happy Holidays--Animated! A Worldwide Encyclopedia of Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa and New year's Cartoons on Television and Picture show. McFarland & Co. p. 171. ISBN9781476672939.

- ^ Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (Mirage Studios): "The Christmas Aliens" (Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird; Micro-Series #3: Michelangelo, December 1985), and "Alien Invaders" (Jim Lawson; Tales of the TMNT Vol.2 #53, December 2008)

- ^ Perry, George; Aldridge, Alan (1967). The Penguin Volume of Comics. Penguin.

- ^ "Tony Royle". lambiek.net.

- ^ "JAY-Z : Brooklyn (Go Hard) lyrics". world wide web.lyricsreg.com.

- ^ "Jay-Z Dirt Off Your Shoulder Lyrics". world wide web.lyrics007.com.

- ^ Petski, Denise (Apr 4, 2016). "'Daily Prove With Trevor Noah' Adds Michelle Wolf Equally On-Air Contributor & Author". Deadline.com . Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Blumenfeld, Zach (Apr 4, 2016). "Comedian Michelle Wolf Joins The Daily Evidence As Writer, Contributor". Paste . Retrieved Apr 9, 2016.

- ^ "Boston University: Howard Gotlieb Archive Research Middle: Harold Greyness Drove". Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ^ "IDW's The Complete Little Orphan Annie Begins in Feb", IDW Publishing press release via Newsarama.com, June 25, 2007 Archived July 2, 2007, at the Wayback Motorcar

Further reading [edit]

- Harvey, Robert C. The Art of the Funnies: An Aesthetic History. (Jackson: Academy Press of Mississippi, 1994), esp. 99–103.

- Cole, Shirley Bell. Acting Her Age: My Ten Years as a Ten-Year-Old: My Memories every bit Radio'southward Little Orphan Annie. Lunenburg, Vermont: Stinehour Press, 2005.

External links [edit]

- Little Orphan Annie at Don Markstein'due south Toonopedia. Archived from the original on Apr 4, 2012.

- The Official Little Orphan Annie Home Page

- Picayune Orphan Annie comic strip pinbacks

- Jensen, Trevor. Footling Orphan Annie' radio actress, Shirley Bong Cole obituary, Chicago Tribune, January 27, 2010.

- Stedman. Raymond William. And a Trivial Child Shall Lead Them

- The Eternal Orphan Annie past Steve Stiles

- The Comics Journal - Harold Gray and the Limits of Conservative Anti-Racism by Jeet Herr

- The Comics Journal - The Orphan's Epic by R.C. Harvey

- Inside Higher Ed - Drawing Conservatism by Scott McLemee

Audio [edit]

- Footling Orphan Annie opening theme

- Little Orphan Annie 31 episodes Cyberspace Archive

- Fiorello La Guardia reads Little Orphan Annie on WNYC during the 1945 newspaper strike

bennettclictithe75.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Orphan_Annie

0 Response to "What Is Little Orphan Annie Hand Drawn Strip Art Worth"

Postar um comentário